Exhibit covariation characteristics in the habitat changes of Sardinops melanostictus and Scomber japonicus in the northwestern Pacific Ocean under ENSO event

-

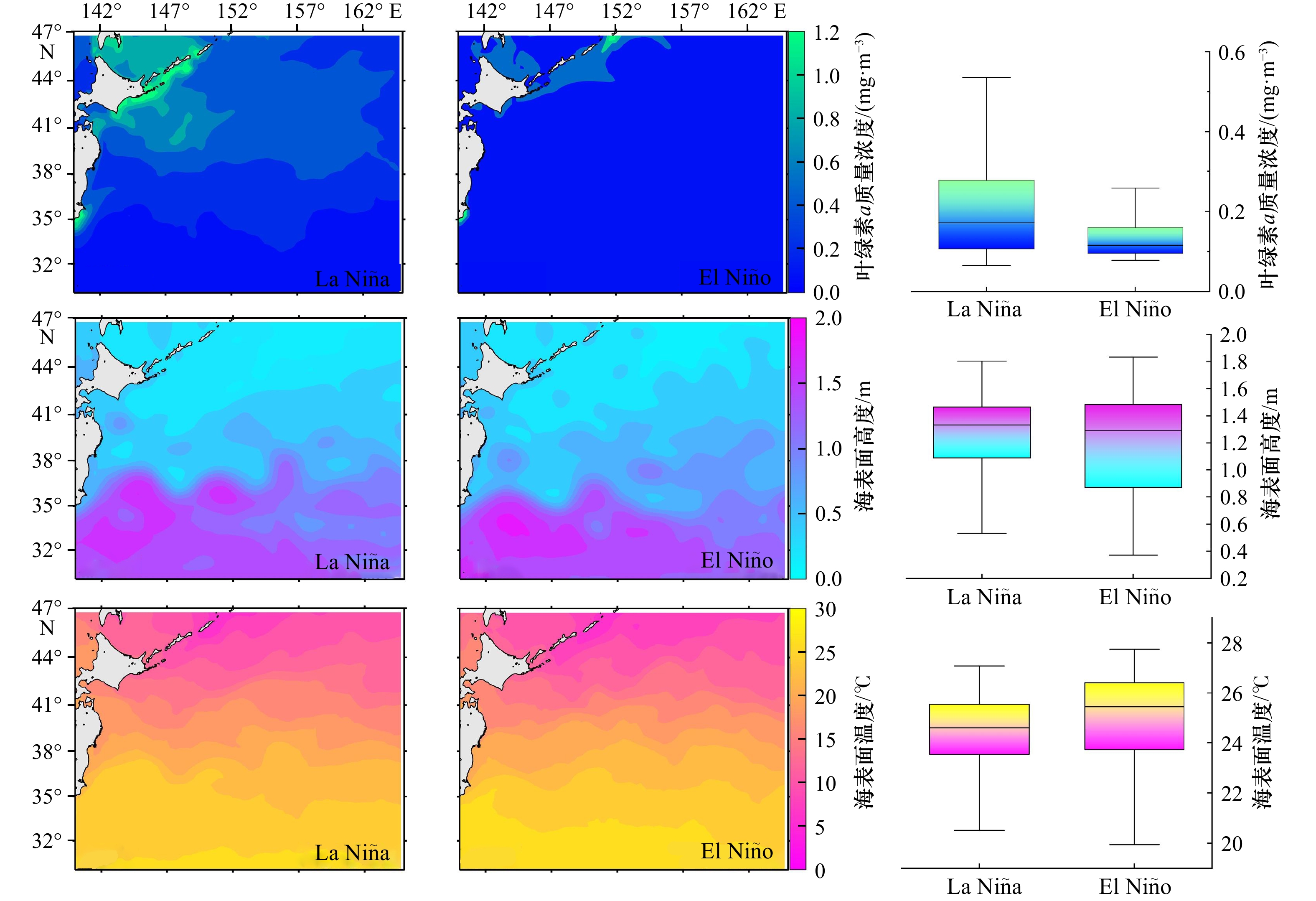

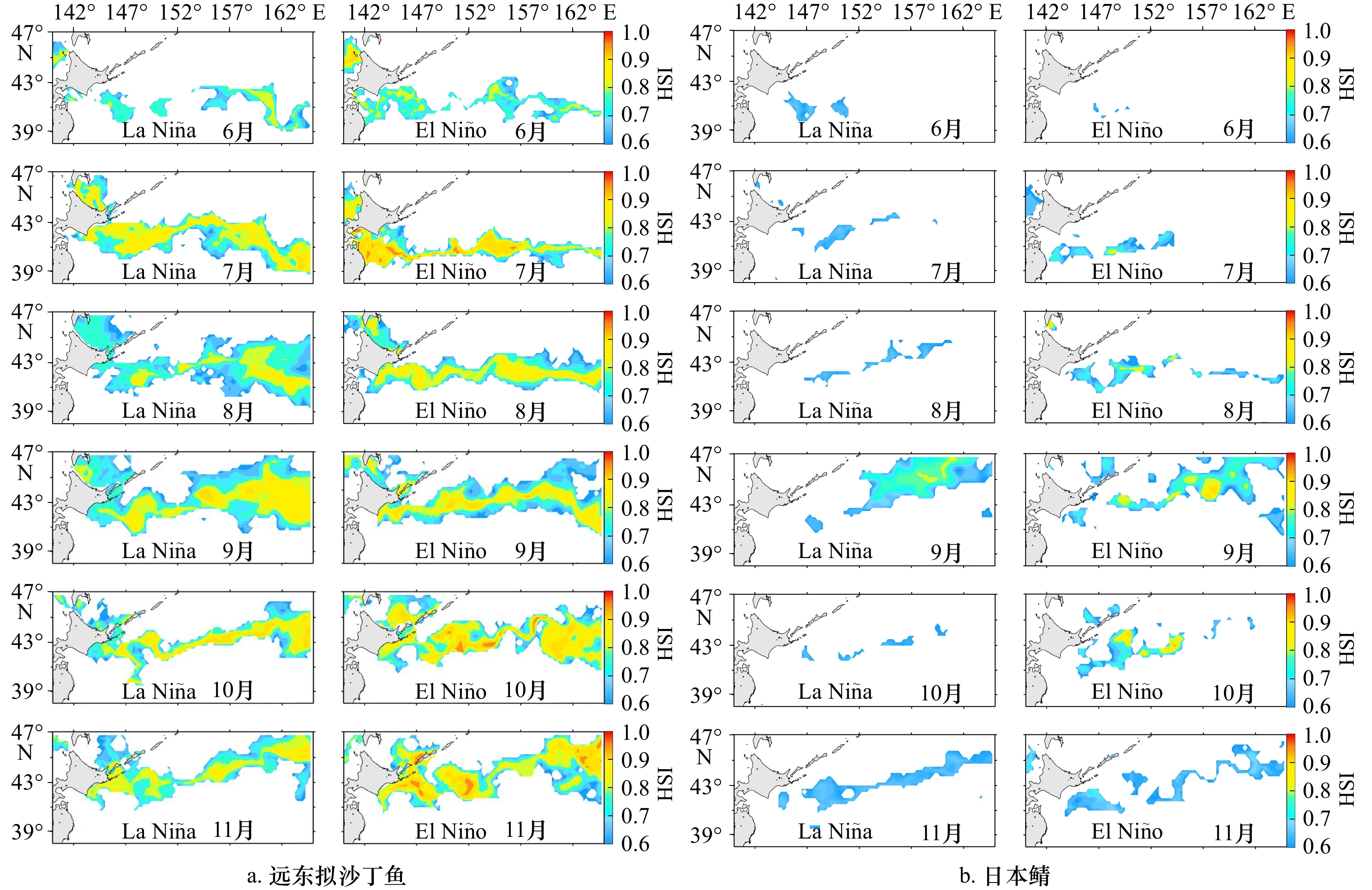

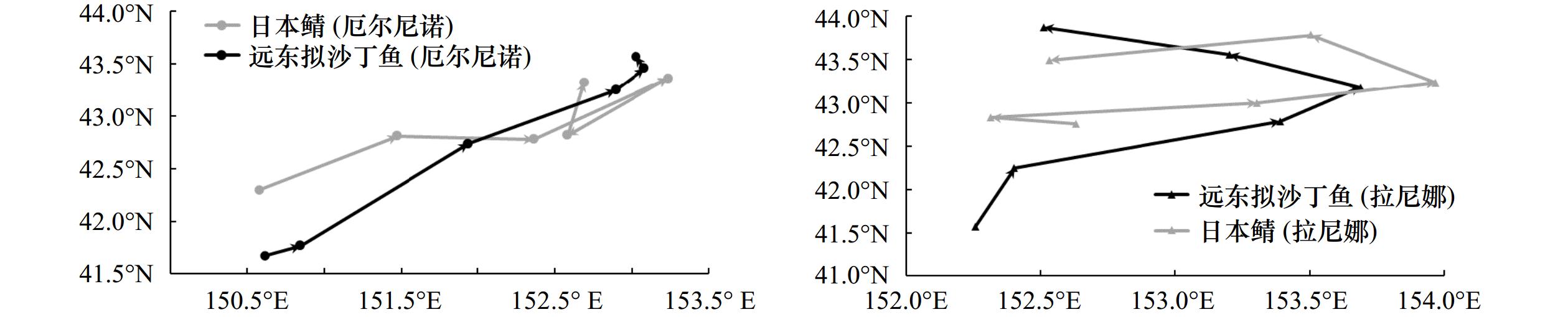

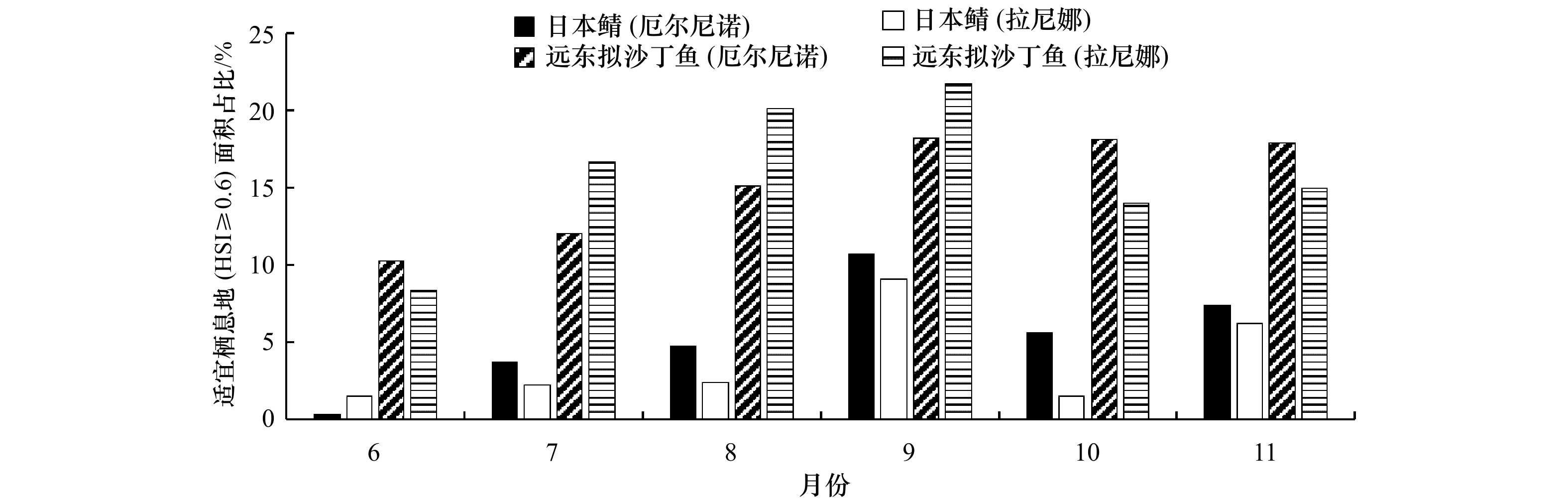

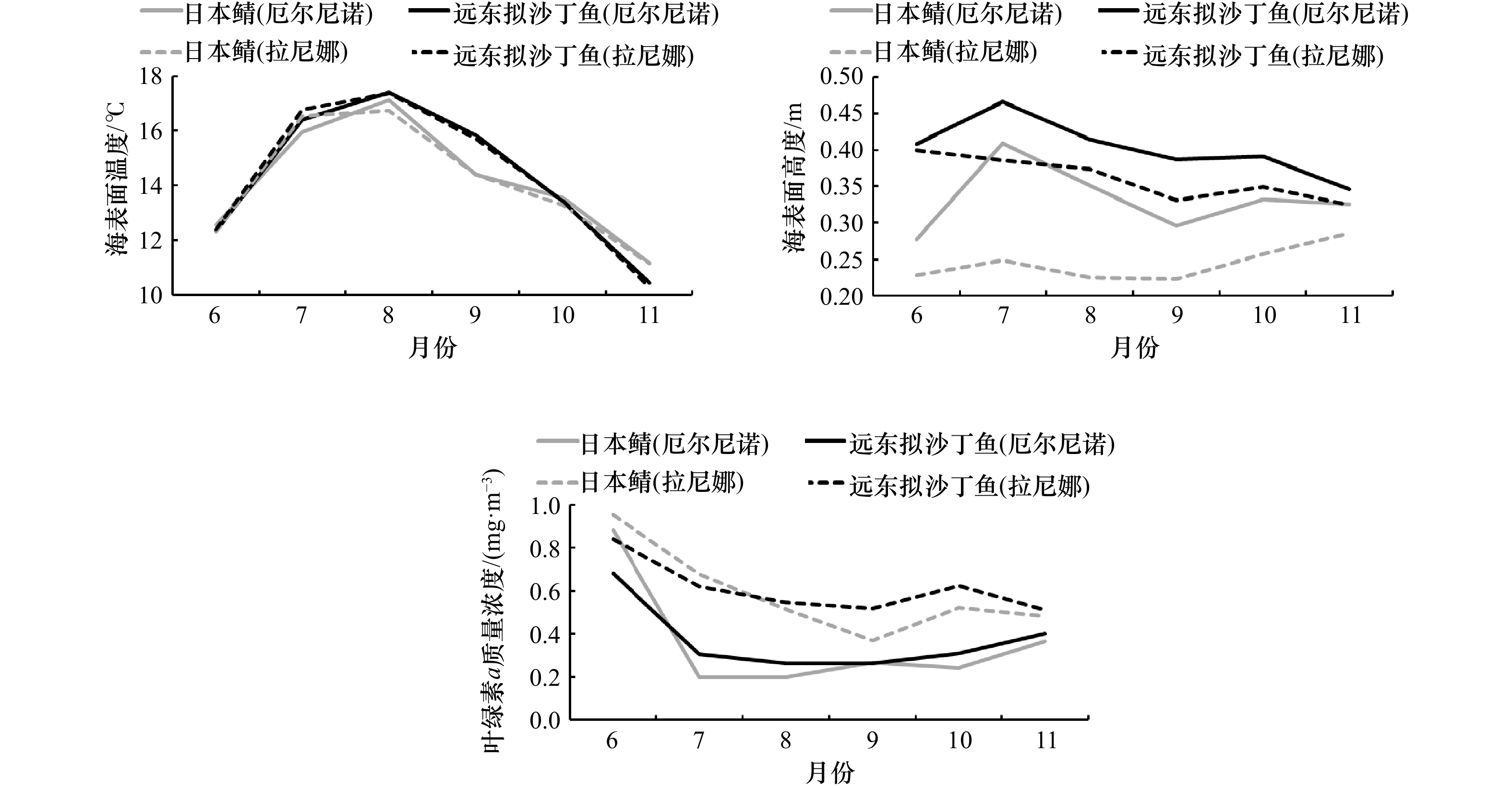

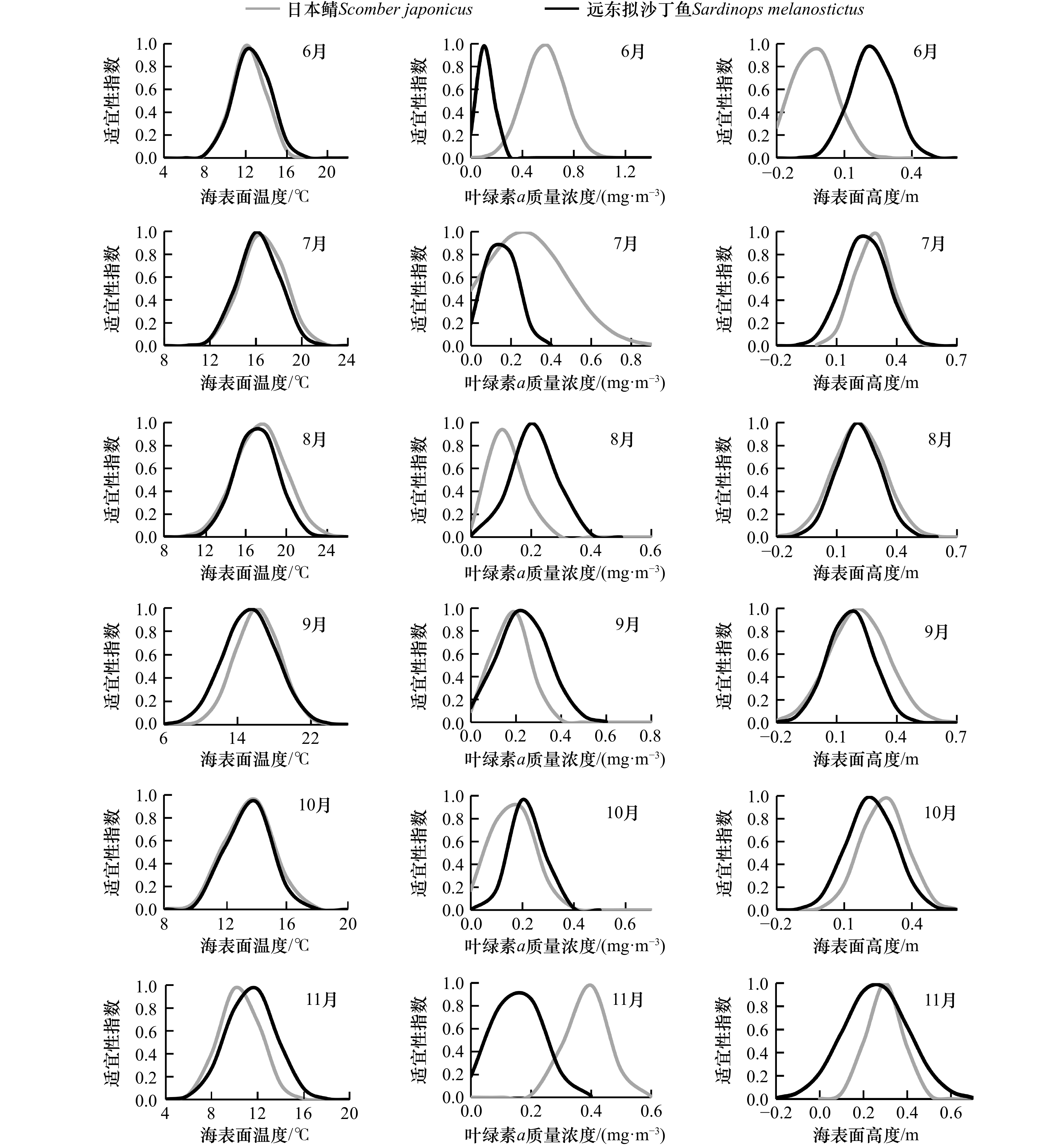

摘要: 远东拟沙丁鱼(Sardinops melanostictus)和日本鲭(Scomber japonicus)是西北太平洋海域重要的关联经济物种,探究二者栖息地变动的关联性有利于合理开发和管理渔业资源。本研究利用2017−2021年6−11月西北太平洋海域远东拟沙丁鱼和日本鲭的渔业数据,结合海表面温度、海表面高度和叶绿素a质量浓度3个关键环境变量分别构建不同权重的栖息地模型,并利用2021年的渔业数据进行验证。选取最优模型预测不同厄尔尼诺与南方涛动(El Niño-Southern Oscillation, ENSO)事件下远东拟沙丁鱼和日本鲭的最适栖息地分布,分析二者在不同ENSO事件下最适栖息地时空分布的差异性和同步性。结果表明:在不同ENSO事件下远东拟沙丁鱼适宜生境面积(高于15%)均高于日本鲭适宜生境面积(低于6%);但远东拟沙丁鱼在拉尼娜事件下最适栖息地面积增长率高于厄尔尼诺事件,前者增长率为0.197,后者增长率为0.123,相反,日本鲭在拉尼娜事件下增长率低于厄尔尼诺事件,前者增长率为1.114,后者增长率为2.082;当远东拟沙丁鱼和日本鲭的分布位置接近时,会促进二者栖息地的适宜条件,当二者分布位置相距较远时会一定程度上抑制日本鲭栖息地面积的增加。远东拟沙丁鱼和日本鲭适宜面积在不同ENSO事件下协同变化特征可能与二者种间关系(竞争/捕食−被捕食)和西北太平洋海域海流分布情况有关。Abstract: The Sardinops melanostictus and the Scomber japonicus are important economic species in the northwestn Pacific Ocean, and exploring the correlation between their habitat changes is conducive to the rational development and management of fishery resources. This study utilizes fishery data of Sardinops melanostictus and Scomber japonicus in the northwestern Pacific Ocean from June to November between 2017 and 2021. By incorporating three key environmental variables, namely sea surface temperature, sea surface height, and chlorophyll a mass concentration, habitat models with different weights are constructed. The models are then validated using fishery data from 2021. The optimal models are selected to predict the most suitable habitat distribution of Sardinops melanostictus and Scomber japonicus under different El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) events. The study analyzes the differences and synchronicity in the spatial and temporal distribution of the most suitable habitat between the two species under different ENSO events. The results indicate that the suitable habitat area of Sardinops melanostictus (above 15%) was higher than that of Scomber japonicus (less than 6%) under different ENSO events; however, the growth rate of the most suitable habitat area for Sardinops melanostictus under La Niña events is higher than that of El Niño events. The former has a growth rate of 0.197 and the latter has a growth rate of 0.123, on the contrary, the growth rate of Scomber japonicus under the La Niña event is lower than that of El Niño event, the former has a growth rate of 1.114 and the latter has a growth rate of 2.082; additionally, when the distribution locations of Sardinops melanostictus and Scomber japonicus are close to each other, it promotes favorable conditions for their habitats. On the other hand, when the distribution locations are far apart, it somewhat inhibits the increase in the suitable habitat area for Scomber japonicus. The co-variation of suitable habitat areas for Sardinops melanostictus and Scomber japonicus under different ENSO events may be related to their interspecies relationship (competition/predation-prey) and the distribution of ocean currents in the northwestern Pacific Ocean.

-

Key words:

- Sardinops melanostictus /

- Scomber japonicus /

- northwestern Pacific Ocean /

- El Niño /

- La Niña /

- habitat area

-

表 1 渔业数据中建模和验证样本量

Tab. 1 Model and validate sample sizes in fishery data

物种 年份 样本量 6月 7月 8月 9月 10月 11月 远东拟沙丁鱼 2017 1 520 1 679 1 518 1 374 1 183 1 083 日本鲭 2017 1 616 1 686 1 538 1 311 1 095 1 078 远东拟沙丁鱼 2018 573 916 431 409 345 279 日本鲭 2018 1 681 1 653 1 068 1 047 721 471 远东拟沙丁鱼 2019 470 460 437 417 285 288 日本鲭 2019 510 543 518 439 339 298 远东拟沙丁鱼 2020 806 943 870 619 574 571 日本鲭 2020 636 773 643 534 731 647 远东拟沙丁鱼 2021 1 668 2 247 1 921 1 924 1 596 1 108 日本鲭 2021 886 810 316 374 633 497 注:“样本量”为2017−2021年各月作业天数的总和;2017−2020年的数据为建模数据,2021年的数据为验证数据。 表 2 不同关键环境变量的不同权重方案

Tab. 2 Different scenarios for the weights of the key environment variables

不同权重方案 海表面温度 海表面高度 叶绿素a质量浓度 方案一 0 1 0 方案二 0 0 1 方案三 0.1 0.8 0.1 方案四 0.1 0.1 0.8 方案五 0.25 0.5 0.25 方案六 0.25 0.25 0.5 方案七 0.5 0.25 0.25 方案八 0.333 0.333 0.333 方案九 0.8 0.1 0.1 方案十 1 0 0 表 3 远东拟沙丁鱼和日本鲭SI模型拟合公式

Tab. 3 Fitting formula of SI models for Sardinops melanostictus and Scomber japonicus

月份 物种 SI 模型 R2 p 6月 远东拟沙丁鱼 SISST = exp[− 0.064 ×(XSST − 11.584)2] 0.795 <0.05 SIChl a = exp[− 33.686 ×(XChl a − 0.64)2] 0.966 <0.01 SISSH = exp[− 40.087 ×(XSSH − 0.237)2] 0.972 <0.01 日本鲭 SISST = exp[− 0.087 ×(XSST − 12.2)2] 0.795 <0.05 SIChl a = exp[− 141.335 ×(XChl a − 0.17)2] 0.902 <0.01 SISSH = exp[− 81.949 ×(XSSH − 0.228)2] 0.911 <0.01 7月 远东拟沙丁鱼 SISST = exp[− 0.069 ×(XSST − 16.429)2] 0.966 <0.01 SIChl a = exp[− 11.607 ×(XChl a − 0.267)2] 0.938 <0.01 SISSH = exp[− 54.679 ×(XSSH − 0.286)2] 0.976 <0.01 日本鲭 SISST = exp[− 0.069 ×(XSST − 15.658)2] 0.906 <0.01 SIChl a = exp[− 84.642 ×(XChl a − 0.195)2] 0.883 <0.05 SISSH = exp[− 66.081 ×(XSSH − 0.3)2] 0.961 <0.01 8月 远东拟沙丁鱼 SISST = exp[− 0.052 ×(XSST − 18.194)2] 0.987 <0.01 SIChl a = exp[− 204.505 ×(XChl a − 0.113)2] 0.890 <0.01 SISSH = exp[− 34.281 ×(XSSH − 0.303)2] 0.958 <0.01 日本鲭 SISST = exp[− 0.053 ×(XSST − 18.195)2] 0.957 <0.01 SIChl a = exp[− 51.625 ×(XChl a − 0.233)2] 0.926 <0.01 SISSH = exp[− 48.229 ×(XSSH − 0.297)2] 0.981 <0.01 9月 远东拟沙丁鱼 SISST = exp[− 0.053 ×(XSST − 15.85)2] 0.775 <0.05 SIChl a = exp[− 16.853 ×(XChl a − 0.096)2] 0.949 <0.01 SISSH = exp[− 87.937 ×(XSSH − 0.293)2] 0.918 <0.01 日本鲭 SISST = exp[− 0.027 ×(XSST − 17.05)2] 0.880 <0.01 SIChl a = exp[− 44.535 ×(XChl a − 0.294)2] 0.961 <0.01 SISSH = exp[− 30.036 ×(XSSH − 0.301)2] 0.919 <0.01 10月 远东拟沙丁鱼 SISST = exp[− 0.121 ×(XSST − 13.352)2] 0.875 <0.05 SIChl a = exp[− 83.825 ×(XChl a − 0.271)2] 0.981 <0.01 SISSH = exp[− 59.476 ×(XSSH − 0.318)2] 0.922 <0.01 日本鲭 SISST = exp[− 0.115 ×(XSST − 12.985)2] 0.944 <0.01 SIChl a = exp[− 45.493 ×(XChl a − 0.277)2] 0.833 <0.01 SISSH = exp[− 67.404 ×(XSSH − 0.313)2] 0.965 <0.01 11月 远东拟沙丁鱼 SISST = exp[− 0.158 ×(XSST − 10.131)2] 0.709 <0.05 SIChl a = exp[− 180.099 ×(XChl a − 0.392)2] 0.983 <0.01 SISSH = exp[− 65.196 ×(XSSH − 0.317)2] 0.857 <0.05 日本鲭 SISST = exp[− 0.136 ×(XSST − 10.817)2] 0.735 <0.01 SIChl a = exp[− 135.492 ×(XChl a − 0.19)2] 0.852 <0.01 SISSH = exp[− 54.85 ×(XSSH − 0.326)2] 0.878 <0.05 表 4 厄尔尼诺(2018年)和拉尼娜(2021年)事件下6−11月远东拟沙丁鱼和日本鲭各月适宜栖息地(HSI≥0.6)面积增长率

Tab. 4 The growth rate of suitable habitat area (HSI ≥ 0.6) of Sardinops melanostictus and Scomber japonicus in El Niño event (2018) and La Niña event (2021) from June to November

物种 气候事件 7月 8月 9月 10月 11月 均值 远东拟沙丁鱼 El Niño 0.170 0.257 0.205 −0.004 −0.012 0.123 La Niña 0.984 0.210 0.080 −0.357 0.067 0.197 日本鲭 El Niño 9.041 0.291 1.240 −0.470 0.309 2.082 La Niña 0.485 0.052 2.826 −0.830 3.038 1.114 -

[1] Klyashtorin L B. Long-term climate change and main commercial fish production in the Atlantic and Pacific[J]. Fisheries Research, 1998, 37(1/3): 115−125. [2] Lecomte F, Grant W S, Dodson J J, et al. Living with uncertainty: genetic imprints of climate shifts in East Pacific anchovy ( Engraulis mordax) and sardine ( Sardinops sagax)[J]. Molecular Ecology, 2004, 13(8): 2169−2182. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02229.x [3] 刘思源, 张衡, 杨超, 等. 西北太平洋远东拟沙丁鱼与日本鲭种群动态特征及其与环境因子关系研究进展[J]. 大连海洋大学学报, 2023, 38(2): 357−368.Liu Siyuan, Zhang Heng, Yang Chao, et al. Relationship between stock dynamics and environmental variability for Japanese sardine ( Sardinops sagax) and chub mackerel ( Scomber japonicus) in the Northwest Pacific Ocean: a review[J]. Journal of Dalian Ocean University, 2023, 38(2): 357−368. [4] Hiyama Y, Yoda M, Ohshimo S. Stock size fluctuations in chub mackerel ( Scomber japonicus) in the East China Sea and the Japan/East Sea[J]. Fisheries Oceanography, 2002, 11(6): 347−353. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2419.2002.00217.x [5] Contreras-Reyes J E, Canales T M, Rojas P M. Influence of climate variability on anchovy reproductive timing off northern Chile[J]. Journal of Marine Systems, 2016, 164: 67−75. doi: 10.1016/j.jmarsys.2016.08.006 [6] 冯志萍, 张艳婧, 余为, 等. 智利外海智利竹筴鱼与茎柔鱼栖息地变动对ENSO事件响应的差异[J]. 中国水产科学, 2021, 28(9): 1195−1207.Feng Zhiping, Zhang Yanjing, Yu Wei, et al. Differences in habitat pattern response to various ENSO events in Trachurus murphyi and Dosidicus gigas located outside the exclusive economic zones of Chile[J]. Journal of Fishery Sciences of China, 2021, 28(9): 1195−1207. [7] Yatsu A, Kawabata A. Reconsidering Trans-Pacific “synchrony” in population fluctuations of sardines[J]. Bulletin of the Japanese Society of Fisheries Oceanography, 2017, 81(4): 271−283. [8] Bai Xuan, Gao Li, Choi S. Exploring the response of the Japanese sardine ( Sardinops melanostictus) stock-recruitment relationship to environmental changes under different structural models[J]. Fishes, 2022, 7(5): 276. doi: 10.3390/fishes7050276 [9] Petatán-Ramírez D, Ojeda-Ruiz M Á, Sánchez-Velasco L, et al. Potential changes in the distribution of suitable habitat for Pacific sardine ( Sardinops sagax) under climate change scenarios[J]. Deep-Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 2019, 169−170: 104632. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2019.07.020 [10] Liu Shuhao, Tian Yongjun, Liu Yang, et al. Development of a prey-predator species distribution model for a large piscivorous fish: a case study for Japanese Spanish mackerel Scomberomorus niphonius and Japanese anchovy Engraulis japonicus[J]. Deep-Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 2023, 207: 105227. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2022.105227 [11] 刘思源, 张衡, 杨超, 等. 基于最大熵模型的西北太平洋远东拟沙丁鱼和日本鲭栖息地差异[J]. 上海海洋大学学报, 2023, 32(4): 806−817.Liu Siyuan, Zhang Heng, Yang Chao, et al. Differences in habitat distribution of Sardinops melanostictus and Scomber japonicus in the Northwest Pacific based on a maximum entropy model[J]. Journal of Shanghai Ocean University, 2023, 32(4): 806−817. [12] Vadas R L Jr, Orth D J. Formulation of habitat suitability models for stream fish guilds: do the standard methods work?[J]. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, 2001, 130(2): 217−235. doi: 10.1577/1548-8659(2001)130<0217:FOHSMF>2.0.CO;2 [13] Bordalo-Machado P. Fishing effort analysis and its potential to evaluate stock size[J]. Reviews in Fisheries Science, 2006, 14(4): 369−393. doi: 10.1080/10641260600893766 [14] Li Gang, Chen Xinjun, Lei Lin, et al. Distribution of hotspots of chub mackerel based on remote-sensing data in coastal waters of China[J]. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 2014, 35(11/12): 4399−4421. [15] Van Der Lee G E M, Van Der Molen D T, Van Den Boogaard H F P, et al. Uncertainty analysis of a spatial habitat suitability model and implications for ecological management of water bodies[J]. Landscape Ecology, 2006, 21(7): 1019−1032. doi: 10.1007/s10980-006-6587-7 [16] Chang Y J, Sun Chilu, Chen Yong, et al. Habitat suitability analysis and identification of potential fishing grounds for swordfish, Xiphias gladius, in the South Atlantic Ocean[J]. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 2012, 33(23): 7523−7541. doi: 10.1080/01431161.2012.685980 [17] Xue Ying, Guan Lisha, Tanaka K, et al. Evaluating effects of rescaling and weighting data on habitat suitability modeling[J]. Fisheries Research, 2017, 188: 84−94. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2016.12.001 [18] Yu Wei, Guo Ai, Zhang Yang, et al. Climate-induced habitat suitability variations of chub mackerel Scomber japonicus in the East China Sea[J]. Fisheries Research, 2018, 207: 63−73. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2018.06.007 [19] 戴澍蔚, 唐峰华, 樊伟, 等. 北太平洋公海日本鲭资源分布及其渔场环境特征[J]. 海洋渔业, 2017, 39(4): 372−382.Dai Shuwei, Tang Fenghua, Fan Wei, et al. Distribution of resource and environment characteristics of fishing ground of Scomber japonicas in the North Pacific high seas[J]. Marine Fisheries, 2017, 39(4): 372−382. [20] 王良明, 李渊, 张然, 等. 西北太平洋日本鲭资源丰度分布与表温和水温垂直结构的关系[J]. 中国海洋大学学报(自然科学版), 2019, 49(11): 29−38.Wang Liangming, Li Yuan, Zhang Ran, et al. Relationship between the resource distribution of Scomber japonicus and seawater temperature vertical structure of northwestern Pacific Ocean[J]. Periodical of Ocean University of China, 2019, 49(11): 29−38. [21] 武胜男, 陈新军. 基于GLM和GAM的日本鲭太平洋群体补充量与产卵场影响因子关系分析[J]. 水产学报, 2020, 44(1): 61−70.Wu Shengnan, Chen Xinjun. Relationship between the recruitment of the Pacific-cohort of chub mackerel ( Scomber japonicus) and the influence factors on the spawning ground based on GLM and GAM[J]. Journal of Fisheries of China, 2020, 44(1): 61−70. [22] Yang Chao, Han Haibin, Zhang Heng, et al. Assessment and management recommendations for the status of Japanese sardine Sardinops melanostictus population in the Northwest Pacific[J]. Ecological Indicators, 2023, 148: 110111. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.110111 [23] Bertrand A, Segura M, Gutiérrez M, et al. From small-scale habitat loopholes to decadal cycles: a habitat-based hypothesis explaining fluctuation in pelagic fish populations off Peru[J]. Fish and Fisheries, 2004, 5(4): 296−316. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2679.2004.00165.x [24] 高川, 陈茂楠, 周路, 等. 2020−2021年热带太平洋持续性双拉尼娜事件的演变[J]. 中国科学: 地球科学, 2022, 52(12): 2353−2372.Gao Chuan, Chen Maonan, Zhou Lu, et al. The 2020−2021 prolonged La Niña evolution in the tropical Pacific[J]. Science China Earth Sciences, 2022, 65(12): 2248−2266. [25] Kaneko H, Okunishi T, Seto T, et al. Dual effects of reversed winter-spring temperatures on year-to-year variation in the recruitment of chub mackerel ( Scomber japonicus)[J]. Fisheries Oceanography, 2019, 28(2): 212−227. doi: 10.1111/fog.12403 [26] 陈丙见, 冯志萍, 余为. 厄尔尼诺和拉尼娜发生期太平洋褶柔鱼秋生群资源丰度的响应研究[J]. 中国水产科学, 2022, 29(11): 1636−1646.Chen Bingjian, Feng Zhiping, Yu Wei. Response of autumn cohort abundance of Japanese common squid ( Todarodes pacificus) during El Niño and La Niña events[J]. Journal of Fishery Sciences of China, 2022, 29(11): 1636−1646. [27] 周茉, 方星楠, 余为, 等. 厄尔尼诺和拉尼娜事件下西北太平洋柔鱼栖息地时空分布差异[J]. 上海海洋大学学报, 2022, 31(4): 984−993.Zhou Mo, Fang Xingnan, Yu Wei, et al. Difference of spatio-temporal distribution of neon flying squid Ommastrephes bartramiii in the Northwest Pacific Ocean under the El Niño and La Niña events[J]. Journal of Shanghai Ocean University, 2022, 31(4): 984−993. [28] Yu Wei, Wen Jian, Chen Xinjun, et al. Effects of climate variability on habitat range and distribution of chub mackerel in the East China Sea[J]. Journal of Ocean University of China, 2021, 20(6): 1483−1494. doi: 10.1007/s11802-021-4760-x [29] Zhang Ronghua, Gao Chuan, Feng Licheng. Recent ENSO evolution and its real-time prediction challenges[J]. National Science Review, 2022, 9(4): nwac052. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwac052 [30] Nishikawa H, Itoh S, Yasuda I, et al. Overlap between suitable nursery grounds for Japanese anchovy ( Engraulis japonicus) and Japanese sardine ( Sardinops melanostictus) larvae[J]. Aquaculture, Fish and Fisheries, 2022, 2(3): 179−188. doi: 10.1002/aff2.39 [31] Gkanasos A, Schismenou E, Tsiaras K, et al. A three dimensional, full life cycle, anchovy and sardine model for the North Aegean Sea (Eastern Mediterranean): validation, sensitivity and climatic scenario simulations[J]. Mediterranean Marine Science, 2021, 22(3): 653−668. doi: 10.12681/mms.27407 [32] Hsu J, Chang Y J, Kitakado T, et al. Evaluating the spatiotemporal dynamics of Pacific saury in the northwestern Pacific Ocean by using a geostatistical modelling approach[J]. Fisheries Research, 2021, 235: 105821. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2020.105821 [33] Yatsu A. Review of population dynamics and management of small pelagic fishes around the Japanese Archipelago[J]. Fisheries Science, 2019, 85(4): 611−639. doi: 10.1007/s12562-019-01305-3 [34] Sogawa S, Hidaka K, Kamimura Y, et al. Environmental characteristics of spawning and nursery grounds of Japanese sardine and mackerels in the Kuroshio and Kuroshio Extension area[J]. Fisheries Oceanography, 2019, 28(4): 454−467. doi: 10.1111/fog.12423 [35] Takasuka A, Oozeki Y, Aoki I. Optimal growth temperature hypothesis: why do anchovy flourish and sardine collapse or vice versa under the same ocean regime?[J]. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 2007, 64(5): 768−776. doi: 10.1139/f07-052 [36] Chavez F P, Ryan J, Lluch-Cota S E, et al. From anchovies to sardines and back: multidecadal change in the Pacific Ocean[J]. Science, 2003, 299(5604): 217−221. doi: 10.1126/science.1075880 [37] 唐峰华, 戴澍蔚, 樊伟, 等. 西北太平洋公海日本鲭( Scomber japonicus)胃含物及其摄食等级研究[J]. 中国农业科技导报, 2020, 22(1): 138−148.Tang Fenghua, Dai Shuwei, Fan Wei, et al. Study on stomach composition and feeding level of chub mackerel in the Northwest Pacific[J]. Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology, 2020, 22(1): 138−148. [38] Oozeki Y, Carranza M Ñ, Takasuka A, et al. Synchronous multi-species alternations between the northern Humboldt and Kuroshio Current systems[J]. Deep-Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 2019, 159: 11−21. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2018.11.018 [39] Nakayama S I, Takasuka A, Ichinokawa M, et al. Climate change and interspecific interactions drive species alternations between anchovy and sardine in the western North Pacific: detection of causality by convergent cross mapping[J]. Fisheries Oceanography, 2018, 27(4): 312−322. doi: 10.1111/fog.12254 [40] Suda M, Watanabe C, Akamine T. Two-species population dynamics model for Japanese sardine Sardinops melanostictus and chub mackerel Scomber japonicus off the Pacific coast of Japan[J]. Fisheries Research, 2008, 94(1): 18−25. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2008.06.012 -

下载:

下载: