Background climate dependence of Atlantic meridional overturning circulation responding to precessional change

-

摘要: 大西洋经向翻转环流(Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation,AMOC)是气候系统重要的组成部分,其强度变化可直接影响南北半球的热量分配,厘清其变化机理对全球变暖背景下的未来预估至关重要。海洋沉积物记录发现,在晚更新世,AMOC的变化与地球岁差周期有紧密联系,但其物理机理尚不清楚。本文利用海洋−大气耦合气候模型—COSMOS(ECHAM5/JSBACH/MPIOM)模型,通过敏感试验,分析在冰盛期冷期和间冰期暖期气候背景下,AMOC对地球岁差变化的响应机理。结果表明:岁差降低引起的北半球夏季太阳辐射增强,会导致间冰期暖期背景下的AMOC显著减弱,但对冰盛期AMOC的影响并不明显。通过进一步分析发现,在间冰期暖期,夏季太阳辐射增强,造成高低纬大西洋海表的升温,同时促进北大西洋高纬度地区的局地降水,两者导致北大西洋表层海水密度降低,共同削弱大西洋深层水生成。而在冰盛期冷期,大西洋高低纬度地区的响应对AMOC的影响反向—副热带升温触发的海盆尺度低压异常,通过其南侧的西风异常削弱大西洋向太平洋的水汽输送,导致净降水增多,海表盐度下降;同时,高纬度升温造成的海冰减少,促进了海洋热丧失,海表失热变重,有利于大西洋深层水的生成,最终两者的共同作用导致AMOC对岁差变化的响应偏弱。本文系统揭示了不同气候背景下,岁差尺度AMOC变化的控制机理,对理解晚更新世AMOC重建记录中持续存在的岁差周期具有重要启示意义。Abstract: The Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC) is an important component of the climate system, of which change in the strength can affect meridional heat distribution between the northern and southern hemispheres. Proxy records show that changes in Atlantic Ocean circulation during the Late Pleistocene is associated with precessional cycle, but its physical mechanism remains unclear. Here we use a fully coupled climate model to investigate dynamics associated with AMOC changes in precessional band under glacial-interglacial climate conditions. Our results show that increase in boreal summer insolation can effectively weaken the AMOC during warm interglacial periods, while this weakening effect is reduced under glacial maximum. We further demonstrate that during the warm interglacial period increase in boreal summer insolation leads to sea surface warming and subpolar rainfall increase in North Atlantic, which jointly reduces sea surface density and hence the strength of deep water formation. During the glacial maximum period, climate responses to precessional change is of anti-phase impacts on the AMOC. At the low latitudes, a low pressure anomaly triggered by subtropical warming weakens atmospheric moisture export from the subtropical Atlantic to Pacific, increasing in net precipitation and hence freshening tropical sea surface in the North Atlantic. At the high latitudes, the warming-induced sea ice retreat promotes ocean heat loss via the enlarged ice-free area, and hence tends to strengthen the vertical mixing. The combined effects of low- and high-latitude responses finally leads to a trivial weakening of the AMOC. Overall, our results provide a systematic understanding of governing mechanism for precessionally-induced AMOC change under glacial-interglacial climatic backgrounds, shedding light on our interpretation of precessional periodicity in reconstructed ocean circulation changes during the Pleistocene.

-

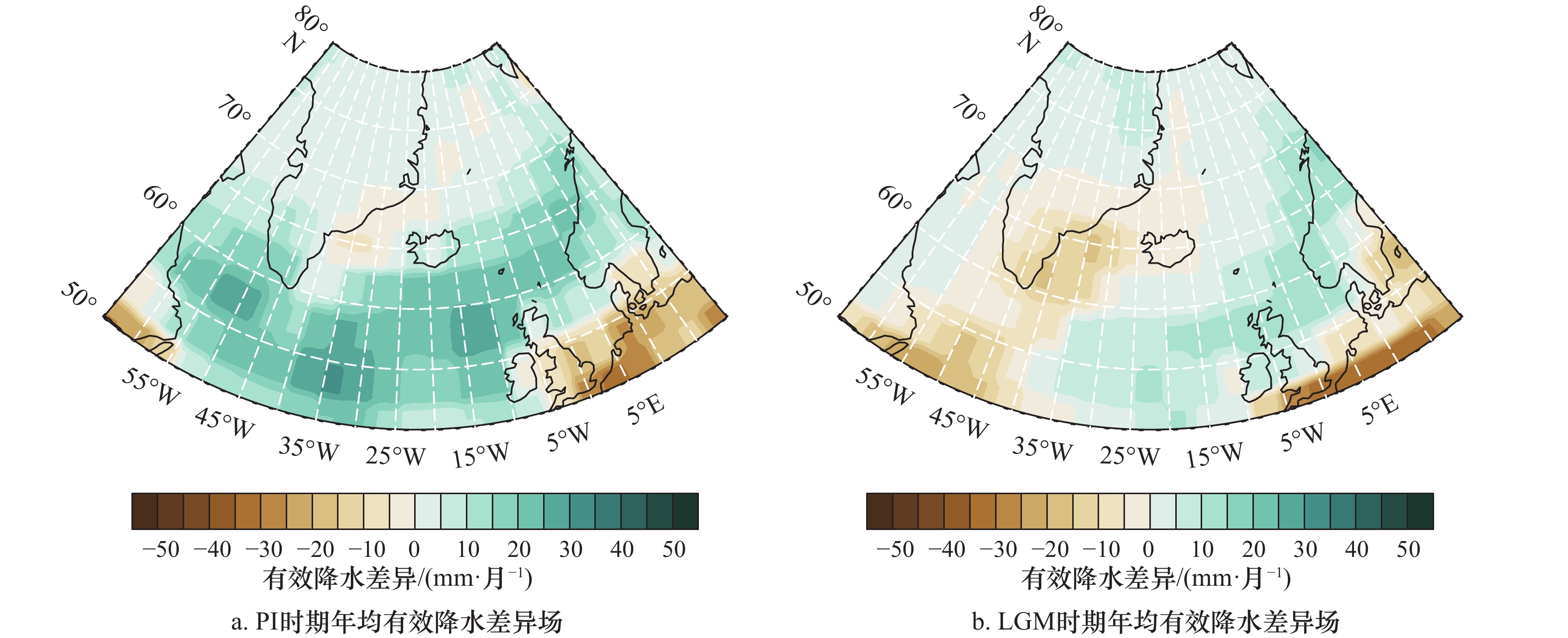

图 3 工业革命前(PI)(a, c)和末次盛冰期(LGM)(b, d)背景下不同气候要素的差异场

a. PI时期夏季海表温度−气压差异场;b. LGM时期夏季海表温度−气压差异场,a和b中填色代表温度差异,黑色等值线代表海平面气压差异(hPa);c. PI时期夏季海表有效降水−水汽输送差异场;d. LGM时期夏季海表有效降水−水汽输送差异场,c和d中填色代表有效降水差异,箭头代表水汽通量差异(单位:kg/(m·s))

Fig. 3 Climate response to changes in precession under pre-industrial (PI) (a, c) and the glacial maximum period (LGM) (b, d) backgrounds

a. Summer sea surface temperature-pressure difference field in PI period; b. the summer sea surface temperature-pressure difference field in LGM period, the coloring represents the temperature difference, and the black isoline represents the sea level pressure difference (hPa) field; c. the summer sea surface effective precipitation-water vapor transport difference field in PI period; d. the summer sea surface effective precipitation-water vapor transport difference field in LGM period, the coloring represents the difference of effective precipitation, and the arrow represents the difference of water vapor flux (unit : kg/(m·s))

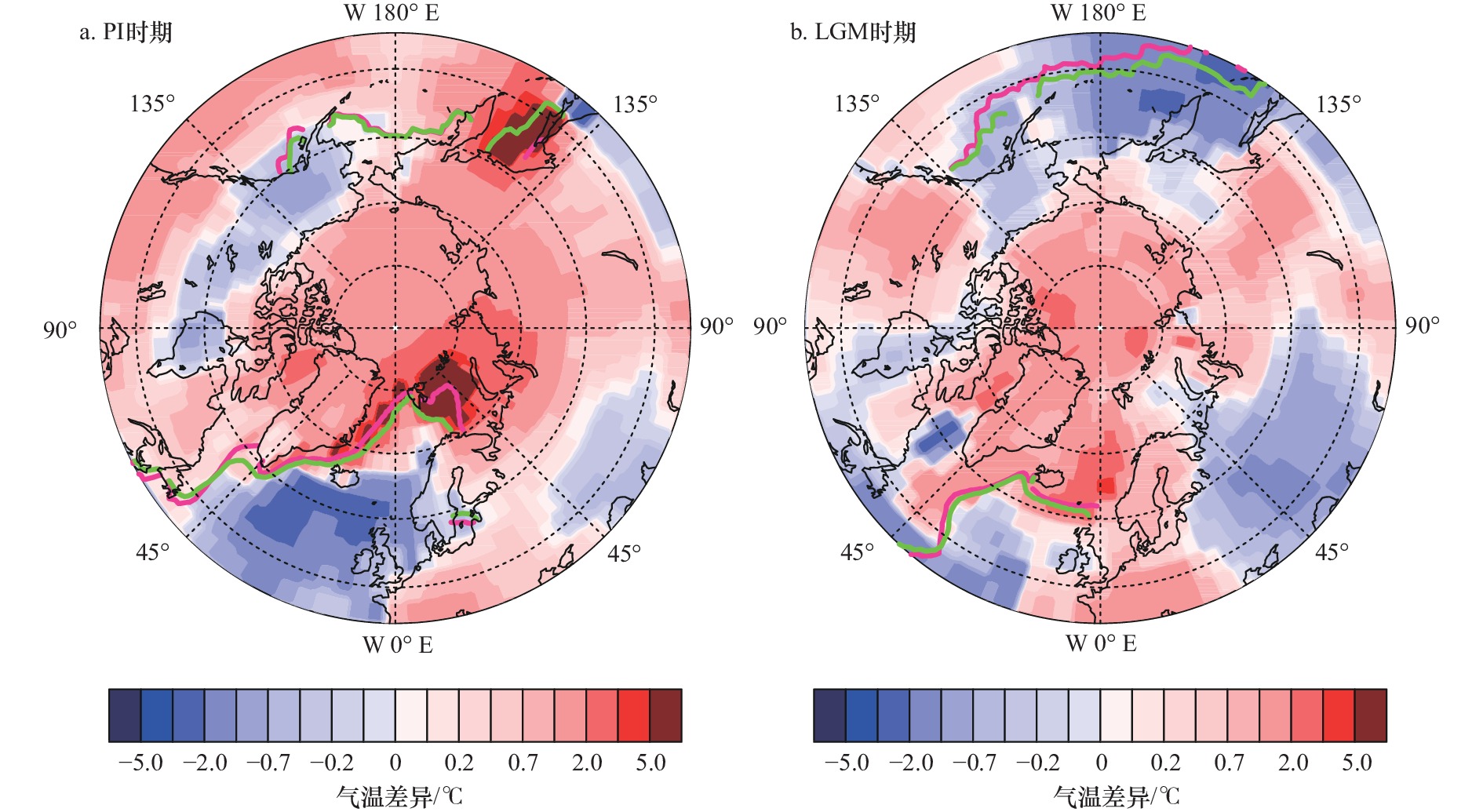

图 6 工业革命前(PI)和末次盛冰期(LGM),最高值与最低值的夏季海冰密集度和冬季垂直混合层深度的差异场

a. PI时期夏季海冰密集度的差异场;b. LGM时期夏季海冰密集度的差异场;c.PI时期冬季垂直混合深度的差异场;d. LGM时期冬季垂直混合深度的差异场。绿线和红线分别对应Pmax和Pmin时期15%海冰密集度分界线

Fig. 6 Anomalous fields of summer sea ice concentration and winter vertical mixing layer depth between Pmin and Pmax under pre-industrial (PI) and the glacial maximum (LGM) conditions

a. The difference field of sea ice concentration in summer in PI period; b. the difference field of sea ice concentration in summer in LGM period; c. the difference field of vertical mixing layer depth in winter in PI period; d. difference field of vertical mixing layer depth in winter in LGM period. Green and red lines represent 15% sea ice concentration in Pmax and Pmin, respectively

图 4 工业革命前(PI)和末次盛冰期(LGM)时期年均海表密度(a, d)、温度(b, e)、盐度(c, f)差异场(上行为强季节背景,下行是弱季节性背景)

Fig. 4 Difference fields of average annual sea surface density (a, d), temperature (b, e) and salinity (c, f) during pre-industrial (PI) and the glacial maximum (LGM) periods (strong seasonal background on the top and weak seasonal background on the bottom)

表 1 具体试验设置

Tab. 1 Specific experimental settings

试验

名称CO2含量

/10−6CH4含量

/10−9N2O含量

/10−9偏心率 倾角

/(°)岁差

/(°)等效海平

面/mORB001 280 760 270 0.04 23.446 90 0 ORB002 280 760 270 0.04 23.446 270 0 ORB01lgm 185 350 200 0.04 24.5 90 116 ORB02lgm 185 350 200 0.04 24.5 270 116 A1 6°~14°N,90°~75°W区域的水汽输送(单位:kg/(m·s))

A1 Integrated water vapor transport across area in 6°−14°N, 90°−75°W (unit: kg/(m·s))

试验名称 水汽输送 年均 春季 夏季 秋季 冬季 5−9月 ORB001 纬向 −126.76 −182.286 −144.391 8.16864 −188.532 −113.281 经向 −9.96022 −26.442 30.3474 12.409 −56.1552 30.7718 合成后 127.151 184.194 147.545 14.8563 196.717 117.386 ORB002 纬向 −175.303 −195.216 −233.976 −73.5462 −198.475 −200.19 经向 −13.9999 −32.7454 31.0561 16.0139 −70.3243 29.0856 合成后 175.861 197.943 236.028 75.2694 210.565 202.292 ORB01lgm 纬向 −92.5443 −159.29 −49.1301 −15.8694 −145.887 −59.1867 经向 −11.8552 −17.5885 27.6077 −12.4783 −44.9616 22.9494 合成后 93.3006 160.258 56.3556 20.1877 152.659 63.4803 ORB02lgm 纬向 −142.635 −176.768 −165.993 −58.9051 −168.875 −146.019 经向 −17.2861 −27.6586 22.6438 −1.23924 −62.8904 20.189 合成后 143.679 178.919 167.53 58.9181 180.205 147.408 -

[1] Johns W E, Baringer M O, Beal L M, et al. Continuous, array-based estimates of Atlantic Ocean heat transport at 26.5°N[J]. Journal of Climate, 2011, 24(10): 2429−2449. doi: 10.1175/2010JCLI3997.1 [2] 李昕容, 杨海军, 王宇星. 大西洋热盐环流减弱对热带太平洋气候平均态及年际变率的影响[J]. 北京大学学报(自然科学版), 2014, 50(2): 242−250.Li Xinrong, Yang Haijun, Wang Yuxing. Influence of a weakened Atlantic thermohaline circulation on tropical Pacific climate mean state and ENSO variability[J]. Acta Scientiarum Naturalium Universitatis Pekinensis, 2014, 50(2): 242−250. [3] 周天军, 张学洪, 王绍武. 大洋温盐环流与气候变率的关系[J]. 科学通报, 2000, 45(11): 1052−1056. doi: 10.1007/BF02884990Zhou Tianjun, Zhang Xuehong, Wang Shaowu. The relationship between the thermohaline circulation and climate variability[J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2000, 45(11): 1052−1056. doi: 10.1007/BF02884990 [4] 邵秋丽, 赵进平. 北欧海深层水的研究进展[J]. 地球科学进展, 2014, 29(1): 42−55. doi: 10.11867/j.issn.1001-8166.2014.01-0042Shao Qiuli, Zhao Jinping. On the deep water of the Nordic seas[J]. Advances in Earth Science, 2014, 29(1): 42−55. doi: 10.11867/j.issn.1001-8166.2014.01-0042 [5] Gong Xun, Zhang Xiangdong, Lohmann G, et al. Higher Laurentide and Greenland ice sheets strengthen the North Atlantic Ocean circulation[J]. Climate Dynamics, 2015, 45(1/2): 139−150. [6] Stommel H. Thermohaline convection with two stable regimes of flow[J]. Tellus, 1961, 13(2): 224−230. doi: 10.3402/tellusa.v13i2.9491 [7] Rahmstorf S. On the freshwater forcing and transport of the Atlantic thermohaline circulation[J]. Climate Dynamics, 1996, 12(12): 799−811. doi: 10.1007/s003820050144 [8] Kuhlbrodt T, Griesel A, Montoya M, et al. On the driving processes of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation[J]. Reviews of Geophysics, 2007, 45(2): RG2001. [9] Huang Boyin, Xue Yan, Kumar A, et al. AMOC variations in 1979−2008 simulated by NCEP operational ocean data assimilation system[J]. Climate Dynamics, 2012, 38(3/4): 513−525. [10] Milanković M. Canon of Insolation and the Ice-age Problem[M]. Belgrade: Royal Serbian Academy, 1941. [11] Zhang Xu, Lohmann G, Knorr G, et al. Abrupt glacial climate shifts controlled by ice sheet changes[J]. Nature, 2014, 512(7514): 290−294. doi: 10.1038/nature13592 [12] Zhang Xu, Knorr G, Lohmann G, et al. Abrupt North Atlantic circulation changes in response to gradual CO2 forcing in a glacial climate state[J]. Nature Geoscience, 2017, 10(7): 518−523. doi: 10.1038/ngeo2974 [13] Lisiecki L E, Raymo M E, Curry W B. Atlantic overturning responses to Late Pleistocene climate forcings[J]. Nature, 2008, 456(7218): 85−88. doi: 10.1038/nature07425 [14] Roeckner E, Bäuml G, Bonaventura L, et al. The atmospheric general circulation model ECHAM 5. Part I: model description[R]. Hamburg: Max-Planck-Institute for Meteorology, 2003. [15] Brovkin V, Raddatz T, Reick C H, et al. Global biogeophysical interactions between forest and climate[J]. Geophysical Research Letters, 2009, 36(7): L07405. [16] Marsland S J, Haak H, Jungclaus J H, et al. The Max-Planck-Institute global ocean/sea ice model with orthogonal curvilinear coordinates[J]. Ocean Modelling, 2003, 5(2): 91−127. doi: 10.1016/S1463-5003(02)00015-X [17] Knorr G, Butzin M, Micheels A, et al. A warm Miocene climate at low atmospheric CO2 levels[J]. Geophysical Research Letters, 2011, 38(20): L20701. [18] Knorr G, Lohmann G. Climate warming during Antarctic ice sheet expansion at the Middle Miocene transition[J]. Nature Geoscience, 2014, 7(5): 376−381. doi: 10.1038/ngeo2119 [19] Stepanek C, Lohmann G. Modelling mid-Pliocene climate with COSMOS[J]. Geoscientific Model Development, 2012, 5(5): 1221−1243. doi: 10.5194/gmd-5-1221-2012 [20] Wei Wei, Lohmann G, Dima M. Distinct modes of internal variability in the global meridional overturning circulation associated with the southern hemisphere westerly winds[J]. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 2012, 42(5): 785−801. doi: 10.1175/JPO-D-11-038.1 [21] Wei Wei, Lohmann G. Simulated Atlantic multidecadal oscillation during the Holocene[J]. Journal of Climate, 2012, 25(20): 6989−7002. doi: 10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00667.1 [22] Abelmann A, Gersonde R, Knorr G, et al. The seasonal sea-ice zone in the glacial southern Ocean as a carbon sink[J]. Nature Communications, 2015, 6: 8136. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9136 [23] Zhang X, Lohmann G, Knorr G, et al. Different ocean states and transient characteristics in Last Glacial Maximum simulations and implications for deglaciation[J]. Climate of the Past, 2013, 9(5): 2319−2333. doi: 10.5194/cp-9-2319-2013 [24] Gong Xun, Knorr G, Lohmann G, et al. Dependence of abrupt Atlantic meridional ocean circulation changes on climate background states[J]. Geophysical Research Letters, 2013, 40(14): 3698−3704. doi: 10.1002/grl.50701 [25] Maier E, Zhang X, Abelmann A, et al. North Pacific freshwater events linked to changes in glacial ocean circulation[J]. Nature, 2018, 559(7713): 241−245. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0276-y [26] Merlis T M, Schneider T, Bordoni S, et al. The tropical precipitation response to orbital precession[J]. Journal of Climate, 2013, 26(6): 2010−2021. doi: 10.1175/JCLI-D-12-00186.1 [27] Ding Zhaomin, Huang Gang, Liu Fei, et al. Responses of global monsoon and seasonal cycle of precipitation to precession and obliquity forcing[J]. Climate Dynamics, 2021, 56(11/12): 3733−3747. [28] Wang Chunzai, Zhang Liping, Lee S K. Response of freshwater flux and sea surface salinity to variability of the Atlantic warm pool[J]. Journal of Climate, 2013, 26(4): 1249−1267. doi: 10.1175/JCLI-D-12-00284.1 [29] Wu Chihua, Tsai P C. Obliquity-driven changes in East Asian seasonality[J]. Global and Planetary Change, 2020, 189: 103161. doi: 10.1016/j.gloplacha.2020.103161 -

下载:

下载: